Playing with intuitive zines as NaNoWriMo prep.

-

Read more: untitled post 156078890

I finally finished the physical mood board for my work in progress.

Here’s a timelapse.

You can see earlier timelapse videos here.

-

Read more: untitled post 156078842

“Fiction has an incredible transformative power. Just because it is quiet and gentle and mostly invisible to the eye does not mean it is not there, this inner strength.”

Elif Shafak

Source: Fiction changes us from within.

-

A Very Merry Unbirthday 🎶

Read more: A Very Merry Unbirthday 🎶I’m still celebrating!

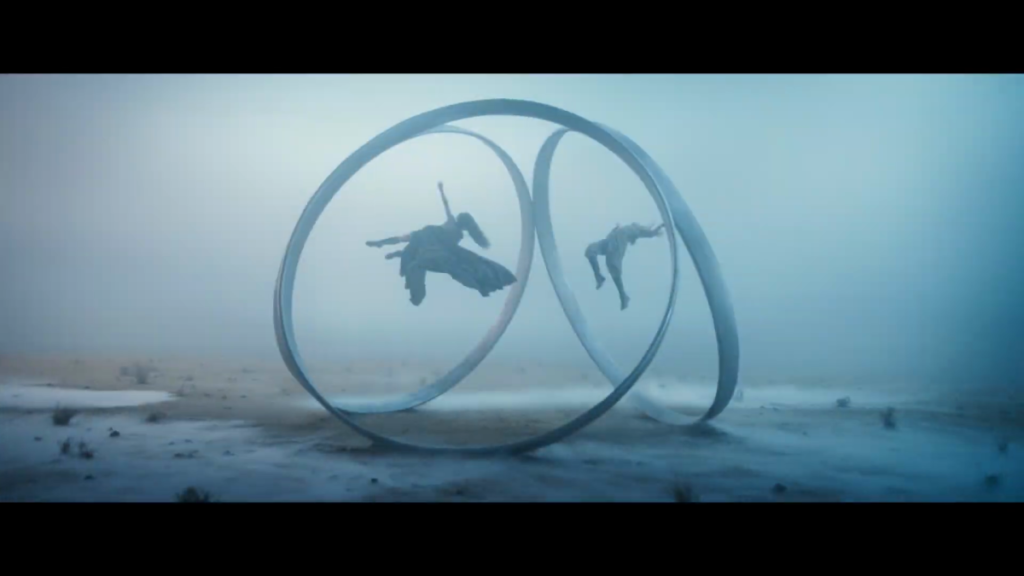

Last week, on my actual birthday, one of my favorite chapters from the Wheel of Time was adapted to screen. So I am having a great month.

As my gift to you, anyone who joins the zine subscription this month, will get a bonus Wheel of Time mini zine. 🥰

If you want to print any of these zines to hype the show you can download them here.

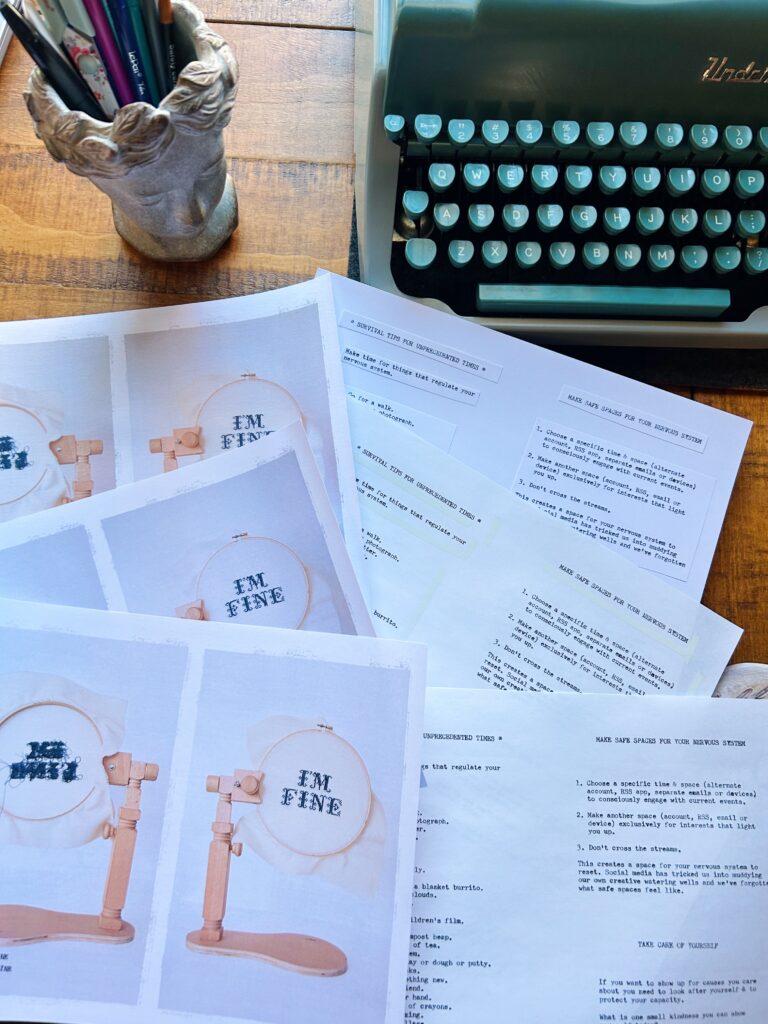

The “I’m Fine” Zine

This month I wrote about creating safe spaces and regulating nervous systems in “unprecedented times.”

You can read the digitized version here.

The work on the cover has been exhibited in several different galleries and is part of the My Brain on Motherhood collection as part of my ARIM.

Sculpture

I’ve also spent a substantial amount of time this month working on a sculpture called Bloom Where You’re Planted from a dead cherry tree.

You can read about the process here.

Here I am cleaning mud off the root.

Time Blind Supports

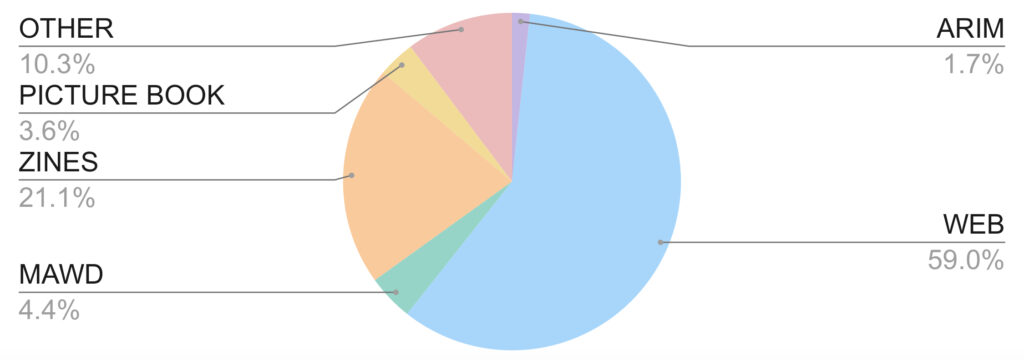

I’m making a concerted effort to spend more time creating and less time on admin this year. One of the tools I’m using for this is logging my time with spreadsheets and charts.

As someone with time blindness I can very easily sink time into something without realizing.

Seeing time visually has made a huge difference for me!

If you’re curious about this process you can click here to read more about what I’m doing and what impact it’s having.

time spent on admin vs. creating in jan, feb & march (so far)

The LOST podcast episode.

Last month, in all my excitement about The Wheel of Time, I completely forgot to tell you I published a ramble podcast. I’ll be doing these on an ad hoc basis moving forward. (If you enjoy listening let me know!)

I haven’t managed to migrated podcast episodes off Substack yet.

Listen here for now.

This is essentially a brain dump I recorded in January reflecting on my creative ecosystem, closing loops, and my intentions for moving into a new year.

When I migrate off Substack I’m thinking of calling this a “Brain Dump Podcast” to remind myself it’s okay to be messy. Here’s some possible podcast art. Not my normal color palette, but maybe my kid’s love of all things rainbow is rubbing off on me.

Wait, there’s more!

Of everything I’m sharing I spent the most time and energy on this.

If you’ve struggled to learn a second language later in life – it may not be for the reasons you think. I’d love to know what neurodivergent folks think of this post.

I also wrote some thoughts about From Where You Dream. A book about storytelling from your unconscious.

Just two posts in the TARDIS time hop this month.

If you have time to check out my 360 VR work I’d love to know what you think.

This Time in 2023

While I was at it I also created a landing page for free resources and printables.

The Compost Heap is handmade without the use of AI. 🐝

Support doing things the old fashioned way by joining my Patrons ($5) and I’ll send paper copies of my zines with the coolest postage stamps I can find.

Test PRINTS FOR MARCH’S “I’m Fine” ZINE Not into snail mail?

Here are other ways you can support.

- Share my blog with a friend. (It’s free!)

- Buy a book or zine from my (new!) shop.

- Link to me in your newsletter.

- Art swap! Let me know if you’d like to swap your art for a zine.

- Send me an email and let me know what resonates.

If you’re reading this in your email inbox you can just hit reply to message me directly. I’d love to hear what you think. It makes it worth the time I put in.

Thanks for being here.

I appreciate you.

P.S. One downside to emailing each month instead of weekly is that there is SO MUCH to cover. I’ve almost given up on sharing links because I have too many to narrow down. But the 15 hours a month I’ve recovered to spend on other projects seems worth the trade off.

If you want a suggestion… Watch the Wheel of Time. 😉

-

From Where You Dream

Read more: From Where You Dreamby Robert Olen Butler

“Please get out of the habit of saying that you’ve got an idea for a short story. Art does not come from ideas. Art does not come from the mind. Art comes from the place where you dream. Art comes from your unconscious; it comes from the white hot center of you.”

The concept of this book is that storytelling comes from your unconscious and not your logical mind. This tracks with the writing process of Ray Bradbury, Dorothea Brande, even Terry Pratchett. It also maps onto the concepts of “day brain” vs. “night brain” writing explored on the podcast Writing Excuses.

But the farther I read into this book the more rigid and didactic Butler’s approach seemed. He needlessly used plot examples requiring a content warning.

I can’t say I wholeheartedly recommend this book, but I do find this concept of taking space to “dream” a story before you write it both liberating and extremely challenging. After setting an intention for more reverie in 2025 I have instead completely rebuilt my website and migrated my newsletter. 🤷

But my best fiction has come from that place of the unconcious. So this is a technique I want to explore.

If you do read this book, take it with a grain of salt. Artists often sound as if their way is the only way because it is the way that works for them.

For their creative ecosystem.

What you or I need may be completely different.

With those caveats here are some passages I found interesting.

“Voice is the embodiment in language of the contents of your unconscious.”

Most artists spend a lot of time and energy trying to find / discover / hone their artistic voice or style. Whereas this suggests that leaning away from analysis and toward the unconscious may bring you closer to your true voice.

“What you forget goes into the compost of the imagination… in a compost heap, things decompose. Your past is full of stories that have been composed in a certain way; that’s what memories are. But only when they decompose are you able to recompose them into new works of art.”

Love a creative compost metaphor of course. He is paraphrasing British novelist Graham Greene here.

“The organic nature of art is such that within the process everything must be utterly malleable, utterly fluent, so that everything ultimately can be brought together; and if there’s anything in there that will not yield, is not open to change, you cannot create the object.”

This is something I’m finding in my own process. I come in with a concept for a story, but the more closely I hold myself within those bounds the worse the writing is. This past year my writing started to enter this dreamspace for the first time. I found the story was moving like shifting tetonic plates.

“Rewriting is redreaming.”

I think the most radical idea in this book is that even editing (normally considered an analytical process) can come from the unconscious.

And should in Butler’s opinion.

As a literature professor he has all the tools for analysis, but claims not to consciously use them. He rereads his books looking for “twangs” and redreams them until it all “thrums.” Even his rewriting process coming from the unconscious.

“The compost heap of the novelist, the repository that exists apart from literal memory, apart from the conscious mind, is mostly made up of direct, sensual life experience.”

More creative compost. Butler has an obsession with sensory details and decries all explanatory words (for emotions, etc.) and here is where you can fall into the trap of taking on his style for your own. Centering on sensory details can certainly make a text richer, but to use them exclusively feels extreme.

It’s a stylistic choice not “good” or “bad” writing as he frames it.

“[Fiction and technique] must first be forgotten…before they can be authentically engaged in the creation of a work of art.”

He’s basically explaining here that all of that analysis (of stories and literature and writing technique) goes in the compost heap and he doesn’t trust it until it’s filtered through dreamspace.

“Desire is the driving force behind plot.”

I think this comes to the heart of his dreamspace technique. Rather than plotting a work analytically (something I am apparently allergic to) he let’s the objective of a character drive the action. This prevents the awkward situation where a character simply does something because the plot requires it.

It’s a bit chicken and the egg.

I don’t think one way is right or wrong. But when you’re done your character had darn well better have a drive for what they are doing. But doesn’t it sound more fun to let character drive your writing rather than the other way around.

“Writers who aspire to a different kind of fiction— entertainment fiction, let’s call it, genre fiction—have never forgotten this necessity of the character’s yearning.”

He is a straight up literary snob here. 🙄

But it’s worth mentioning because this chapter reminded me of musical theatre structure.

Something strongly present in my personal compost heap.

There’s always an “I want” song in Act I.

“[The artist] doesn’t know what she knows about the world until she creates the object… the writing of a work of art is as much an act of exploration as it is expression, an exploration of images, of moment-to-moment sensual experience.”

I think a lot of writers sit down to “write a book” not to “discover a story.”

For all of my criticisms of this book I do think I’ve added some rich humus (with a pile of horse 💩) to my compost heap.

That said, I hesitate to give Butler too much credit. The reason I bought his book was that I was already curious about a more intuitive approach based on Ray Bradbury’s Zen and the Art of Writing.

I gave up marking quotes because I wanted to quote every other line. And ended up too intimidated to write about it at all. Which now feels silly because I’m writing about this book that is a dim reflection of it.

Bradbury very much wrote from this dreamspace and drawing images and characters from his unconcious. I just need to find the fortitude to do it justice when writing about it.

Maybe next month.

Photo Credit: Patrick McManaman

-

Draft no. 4

Read more: Draft no. 4by John McPhee

This book is half writing craft / half memoir. Here are some of his gem’s about writing.

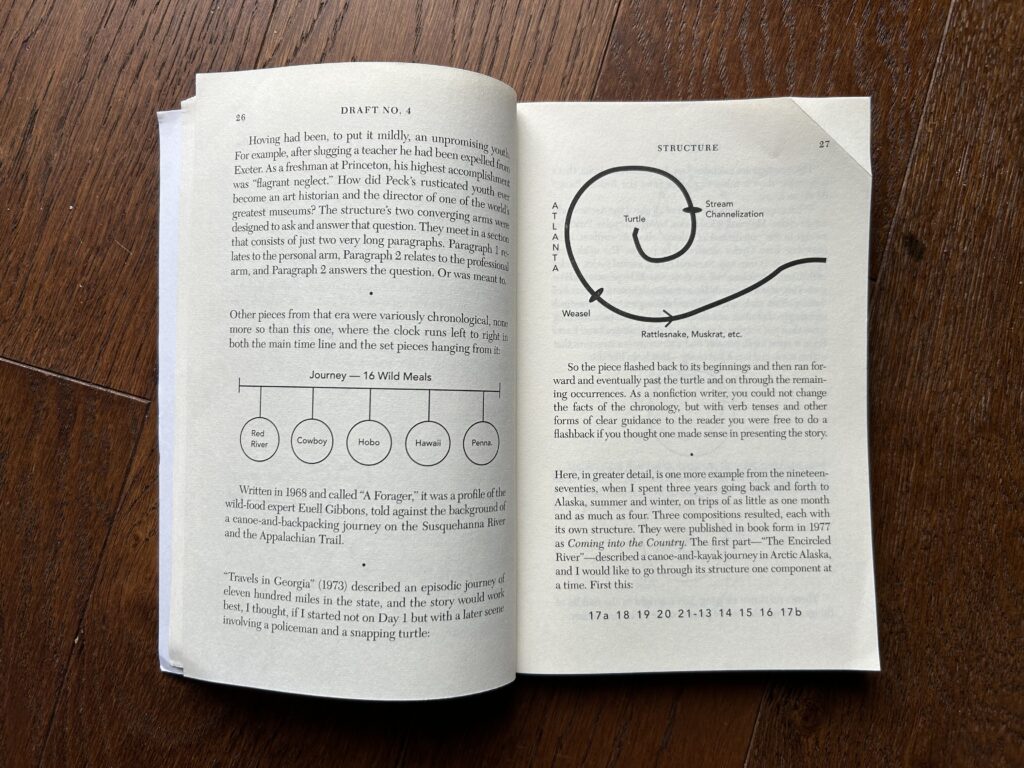

First, one of the graphs that inspired me to buy the book. I am fascinated how he thinks so visually about his structural process.

(The book was second hand and dog eared when I bought it.)Notes on Structure

Almost always there is considerable tension between chronology and theme, and chronology traditionally wins.

McPhee is talking about non fiction here, but this is doubly true for novels.

Readers are not supposed to notice the structure. It is meant to be about as visible as someone’s bones.

a basic criterion for all structures: they should not be imposed upon the material. They should arise from within it.

This is a very actionable step.

Often, after you have reviewed your notes many times and thought through your material, it is difficult to frame much of a structure until you write a lead. You wade around in your notes, getting nowhere. You don’t see a pattern. You don’t know what to do. So stop everything. Stop looking at the notes. Hunt through your mind for a good beginning. Then write it. Write a lead.

I would go so far as to suggest that you should always write your lead (redoing it and polishing it until you are satisfied that it will serve) before you go at the big pile of raw material and sort it into a structure.

I wonder if writing a novel that is underpinned with research and note making could move forward similarly to the process of writing non fiction. I’m curious about this as I am someone who is more comfortable writing non fiction and trying to find my feet with novels.

The lead—like the title—should be a flashlight that shines down into the story. A lead is a promise. It promises that the piece of writing is going to be like this. If it is not going to be so, don’t use the lead.

More stunning imagery. I love the idea of the lead as a flashlight shining down through a story.

Another way to prime the pump is to write by hand… get away from the computer, lie down somewhere with pencil and pad, and think it over. This can do wonders at any point in a piece and is especially helpful when you have written nothing at all. Sooner or later something comes to you. Without getting up, you roll over and scribble on the pad. Go on scribbling as long as the words develop. Then get up and copy what you have written into your computer file.

Another actionable tip. And yet acknowledging what works for him is not universal:

Alternating between handwriting and computer typing almost always moves me along, but that doesn’t mean it will work for you.

Finding Your Style

Young writers find out what kinds of writers they are by experiment.

If they choose from the outset to practice exclusively a form of writing because it is praised in the classroom or otherwise carries appealing prestige, they are vastly increasing the risk inherent in taking up writing in the first place. It is so easy to misjudge yourself and get stuck in the wrong genre.

You avoid that, early on, by writing in every genre. If you are telling yourself you’re a poet, write poems. Write a lot of poems. If fewer than one work out, throw them all away; you’re not a poet. Maybe you’re a novelist. You won’t know until you have written several novels.

This is so interesting. Particularly the bit about getting stuck writing in a way that was praised in school.

Young writers generally need a long while to assess their own variety, to learn what kinds of writers they most suitably and effectively are…

“Though a man be more prone and able for one kind of writing than another, yet he must exercise all.” Ben Jonson

One of my favorite quotes in the book.

No one will ever write in just the way that you do, or in just the way that anyone else does. Because of this fact, there is no real competition between writers. What appears to be competition is actually nothing more than jealousy and gossip. Writing is a matter strictly of developing oneself. You compete only with yourself. You develop yourself by writing. An editor’s goal is to help writers make the most of the patterns that are unique about them.

On omission and selection,

Writing is selection.

… You select what goes in and you decide what stays out. At base you have only one criterion: If something interests you, it goes in—if not, it stays out.

… Forget market research. Never market-research your writing. Write on subjects in which you have enough interest on your own to see you through all the stops, starts, hesitations, and other impediments along the way. Ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material—that much and no more.

Drafting

McPhee on the difference between drafts and a ratio of how long each draft takes that he observed in his own writing over time.

First drafts are slow and develop clumsily because every sentence affects not only those before it but also those that follow. The first draft of my book on California geology took two gloomy years; the second, third, and fourth drafts took about six months altogether. That four-to-one ratio in writing time—first draft versus the other drafts combined—has for me been consistent in projects of any length, even if the first draft takes only a few days or weeks. There are psychological differences from phase to phase, and the first is the phase of the pit and the pendulum. After that, it seems as if a different person is taking over. Dread largely disappears. Problems become less threatening, more interesting. Experience is more helpful, as if an amateur is being replaced by a professional. Days go by quickly and not a few could be called pleasant, I’ll admit.

I’m intrigued to see him using the same metaphor as Neil Gaiman [[Throwing Mud at the Wall]]. I wonder who said it first and if one is referencing the other or if it arose naturally because it is so fitting to the task at hand.

The way to do a piece of writing is three or four times over, never once. For me, the hardest part comes first, getting something—anything—out in front of me. Sometimes in a nervous frenzy I just fling words as if I were flinging mud at a wall.

And in a letter to his daughter (writer Jenny McPhee),

You finish that first awful blurting, and then you put the thing aside. You get in your car and drive home. On the way, your mind is still knitting at the words. You think of a better way to say something, a good phrase to correct a certain problem. Without the drafted version—if it did not exist—you obviously would not be thinking of things that would improve it. In short, you may be actually writing only two or three hours a day, but your mind, in one way or another, is working on it twenty-four hours a day—yes, while you sleep—but only if some sort of draft or earlier version already exists.

In another letter to Jenny,

Dear Jenny: What am I working on? How is it going? Since you asked, at this point I have no confidence in this piece of writing. It tries a number of things I probably shouldn’t be trying. It tries to use the present tense for the immediacy that the present tense develops, but without allowing any verb tense to become befouled in a double orientation of time. It tells its story inside out. Like the ship I’m writing about, it may have a crack in its hull. And I’ve barely started. After four months and nine days of staring into this monitor for what has probably amounted in aggregate to something closely approaching a thousand hours, that’s enough. I’m going fishing.”

Fiction

Art is where you find it. Good writing is where you find it. Fiction, in my view, is much harder to do than fact, because the fiction writer moves forward by trial and error, while the fact writer is working with a certain body of collected material, and can set up a structure beforehand.

“Fiction must stick to facts, and the truer the facts the better the fiction—so we are told.” Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own.

Editing

An editing tip he uses himself and taught his students at Stanford,

You draw a box not only around any word that does not seem quite right but also around words that fulfill their assignment but seem to present an opportunity.

While the word inside the box may be perfectly O.K., there is likely to be an even better word for this situation, a word right smack on the button, and why don’t you try to find such a word? If none occurs, don’t linger; keep reading and drawing boxes, and later revisit them one by one. If there’s a box around “sensitive” because it seems pretentious in the context, try “susceptible.” Why “susceptible”? Because you looked up “sensitive” in the dictionary and it said “highly susceptible.” With dictionaries, I spend a great deal more time looking up words I know than words I have never heard of—at least ninety-nine to one. The dictionary definitions of words you are trying to replace are far more likely to help you out than a scattershot wad from a thesaurus.

On knowing when he is done,

When am I done? I just know. I’m lucky that way. What I know is that I can’t do any better; someone else might do better, but that’s all I can do; so I call it done.

William Shawn, McPhee’s Editor at The New Yorker when asked how he has so much time to work with each writer on the smallest details,

“It takes as long as it takes.”

McPhee’s advice on maintaining your voice when working with editors,

There are people who superimpose their own patterns on the work of writers and seem to think it is their role to force things in the direction they would have gone in if they had been doing the writing. Such people are called editors, and are not editors but rewriters.

My advice is, never stop battling for the survival of your own unique stamp. An editor can contribute a lot to your thoughts but the piece is yours—and ought to be yours—if it is under your name.

And then on how invaluable editors can be,

Editors are counselors and can do a good deal more for writers in the first-draft stage than at the end of the publishing process.

The help is spoken and informal, and includes insight, encouragement, and reassurance with regard to a current project.

Confidence and Imposter Syndrome

If you lack confidence in setting one word after another and sense that you are stuck in a place from which you will never be set free, if you feel sure that you will never make it and were not cut out to do this, if your prose seems stillborn and you completely lack confidence, you must be a writer.

And unless you can identify what is not succeeding—unless you can see those dark clunky spots that are giving you such a low opinion of your prose as it develops—how are you going to be able to tone it up and make it work?

This is encouraging because this is the same reframe I used when returning to fiction writing after giving it up. If I see the problems I can work on fixing them.

Notes on Technology

Howard thought the computer should be adapted to the individual and not the other way around. One size fits one.

Howard was a computer programmer who helped McPhee customize the software he used.

Hat Tip to Austin Kleon

-

A wind rose in Charleston, South Carolina 🍃

Read more: A wind rose in Charleston, South Carolina 🍃“The wind was not the beginning. There are neither beginnings nor endings to the Wheel of Time. But it was a beginning.”

Last week I went on a creative pilgrimage to Charleston, South Carolina.

- I visited a library.

- I saw a tree.

- I met up with my “book club.” *

That’s the easy to digest version.

The facts, if you will.

But this trip was not about facts. It was about metaphysics.

For the uninitiated, metaphysics is:

“the branch of philosophy that deals with the first principles of things, including abstract concepts such as being, knowing, substance, cause, identity, time, and space.”2

This journey was about all of these things in a really intricate and profound way.

But first, let’s take a step back into the late 90s.

Observe Sarah, who has fallen asleep on the bed with a dictionary. Again. To the side of the bed is a stack of large thick blue books and several notebooks. If you thumbed through the notebooks you’d find clumsily written facts and lists of names.

Or carefully calligraphed prophecies.

At this point in my life I had no concept of neurodivergence or autism. But I had fallen for the deepest special interest of my life. When I wasn’t doing schoolwork or working I was thinking about these books.

The Wheel of Time.

I’ve written about this before, but it’s almost impossible to get across how important these books are to me or why. Here’s where metaphysics comes in.

There’s something about connecting with someone’s art that goes beyond the physical plane. Beyond logic.

It would be easy to say I love the characters, the genre, the use of language. That I’m drawn in by the depth of world building, the complexity of the magic system, and the sheer scope of the books. All of these things are true.3

Yet, I don’t think these are why I connect so deeply to this story.

It’s more ephemeral than that.

More metaphysical.

There’s something in me that feels seen by these books.

A sense of belonging and knowing that runs deeper than thought processes. A recognition at the soul level.4

The same feeling as when you meet a friend who just “gets it.” When the things that felt weird and unknowable about you become points of connection.

“You too? I thought it was just me.”

But it’s not just about similarities. Differences form this bond as well. And they expand your worldview. You begin to see the world through the eyes of your friend.

That is how I feel about these books. They see me and they also stretch me.

These characters were my peers. The fact that they weren’t real didn’t make their influence any less impactful.

I read these books at the height of my social anxiety. And I took away important lessons from the Aes Sedai. I saw their confidence and how they carried themselves in the world. I learned that perception can be more powerful than reality. And the that the truth you hear isn’t always the truth you think you hear.

I also saw teenagers leave their village and reshape the world. Everything felt possible.

When I finished the series I put the books on a shelf and didn’t touch them for a decade. (I talked about this a bit in my podcast chat with Morgan Harper Nichols.)

I didn’t realize at the time that my interests are a tool for self regulation and a lens I use to process the world. I had no idea what function they had in my life until they were no longer there.

In 2020 I hit rock bottom.

I couldn’t cope.

Then I started re-reading The Wheel of Time.

I’d forgotten how these books made me feel. I knew I loved them. But I also enjoy other stories and books that don’t have the same resonance. These stories are different.

They are etched into my bones.

When I re-read the Wheel of Time I’m always surprised at the curious mix of what I’ve retained – the details I know as if I lived them. And what became hazy over time.

There’s always something new to notice.

And in a story of 4.4 million words and 2787 distinct named characters I suppose there would be.5

Sometime after that re-read I also reconnected to the Wheel of Time community. I was surprised and delighted to find there were other nerds who still loved these stories as much as I do.

It felt like rediscovering part of myself that I’d forgotten existed. My joy at listening to livestreams on The Dusty Wheel was palpable.. an embodied sense of belonging. “These are my people.”

The more time I spend in this community the more incredible I realize it is.

There’s a generosity in spirit and a value in creative joy that I haven’t seen in other corners of the internet. The more I watched these people nerding out the more I knew I needed to make time and space for this in my own life.

This January I wrote down “Wheel of Time convention” and “Pilgrimage to Robert Jordan’s Notes” as long term goals. It felt impossible at the time, but also important. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine both would happen this year.

Intention invites opportunity.

After winning a ticket to WoT Con this summer one thing led to another and I signed up for Ogier Con – a small gathering of fans who were planning to make the pilgrimage to Charleston…together.

Instead of traveling alone I was destined to go there in community.

The wheel weaves as the wheel wills.

When I made it to the library I found myself reading Wheel of Time manuscripts with Matt Hatch, Tamrylin of Theoryland, Innkeeper of The Dusty Wheel.

In that moment, time collapsed in on itself. I existed in four timelines simultaneously:

- the moment I learned these notes existed

- thinking this trip was impossible

- writing the intention

- holding RJ’s notes in my own hand

Over time other hard core fan freaks joined us at the table. We’d each come with a different purpose.

My purpose was to study Robert Jordan’s creative process.

My curiosity about RJ’s writing process doesn’t come from a desire to replicate it. I could no more write in his particular style than you could teach a bird to swim.

But I’m learning that his process was messier and more intuitive than what I had come to accept as “the right way.” It’s given me inspiration to toss out the rule book and develop a writing process that works for me.

There’s something about the Wheel of Time that reverberates with the storyteller inside me.

It shakes my inner writer awake. I wondered if I’d feel that reading his notes. And I did. The more I learn about Robert Jordan’s writing process the more I see pieces of myself.

Don’t get me wrong. We’re wildly different people. But there are mundane similarities.

Looking at his notes I found lists. Facts, idioms, and so much research. He filled notebooks with information about plants and herbal remedies. Historical and mythological figures.

Other notebooks had a single list and the rest was empty.

(I vow never to feel guilty about abandoning notebooks again.) 😂

These were just the kind of notes I used to keep as a teenager. I had one small green notebook that was a collection of names – especially for writing.

I also have an obsession with collecting what I call colloquialisms. An interest originally sparked by their use in Robert Jordan’s writing, and expanded during my time living abroad.

For example, I love the contrast between

“I feel like I’ve been hit by a Mac truck.” (Mississippi)

and

“I feel like I’ve been pulled through a bush backwards.” (Ireland)

It’s even better with accents, trust me.

I looked up some of the phrases RJ had collected and determined they were from films. I can only imagine that he then studied those to work out how to create his own. He was an expert at this and it made his world feel rich and lived in. For example, a character who grew up in a fishing village says,

“You bore a hole in the boat and worry that it’s raining.”6

I love seeing evidence that Robert Jordan had similar drive to collect information.

There was a conspicuous lack of outlines.

Instead there were plenty of notes in a style that RJ called “rambling.”

These ramble files read almost like freewriting about the story. He seemed to craft his plot on the page. Not in an outline.

The first ramble file I read opened with a few paragraphs about Emonds Field – the houses, the economic structure, the village’s contact with the outside world (peddlers, grain traders, and gleemen.) Then he starts working through details. I love the bits where he asks himself questions or sets down two different options to consider.

“The peddler is dead(?)”7

“Tea: where does it come from?”8

“Lan falls in love with Eguene (?) or with Nyneve (?)”9

“????? the Rods of Dominion ?????”10

Many of Jordan’s early ideas are very different to what happens in the books while others remain unchanged.

I think my writing process could do with a bit more rambling on paper.

I already use freewriting to process experiences in life. So it feels like a natural fit to weave that into my storytelling.

I stayed in the library until a librarian came up quietly and asked, “Did you know we close at 4?” It was 4. I thanked her and packed up. I paused to look at the display outside the library. RJ’s old desktop computer was there with a sticker,

“Any sufficiently advanced technology will be indistinguishable from magic.”

I started a 15 minute walk to the Air B&B my rolling suitcases in tow. Along the way I serendipitously came across Ogier street. The Ogier are a forest dwelling people in the Wheel of Time who have a penchant for long winded stories and info dumps. (Sound familiar?)

I took a photo.

The rest of the weekend was an exploration of Charleston and the places that inspired the books.

We visited the Angel Oak, known affectionately by the fandom as Avendesora, the Wheel of Time’s version of the Tree of Life. I’ve seen live oaks before, but the scale of this one was otherworldly. It’s impossible to convey the sense of scale with a photograph.

The next day we walked the gardens of Harriet McDougal’s home (Robert Jordan’s widow and editor). We were given a tour by Maria Simons (Head of the Brown Ajah). Every time I thought we’d seen it all we would turn a corner or step into a passageway and discover more. A true secret garden.

I took photos of flowers to plant in my own garden next year (including these tithonia which the butterflies loved… I even spotted a monarch.)

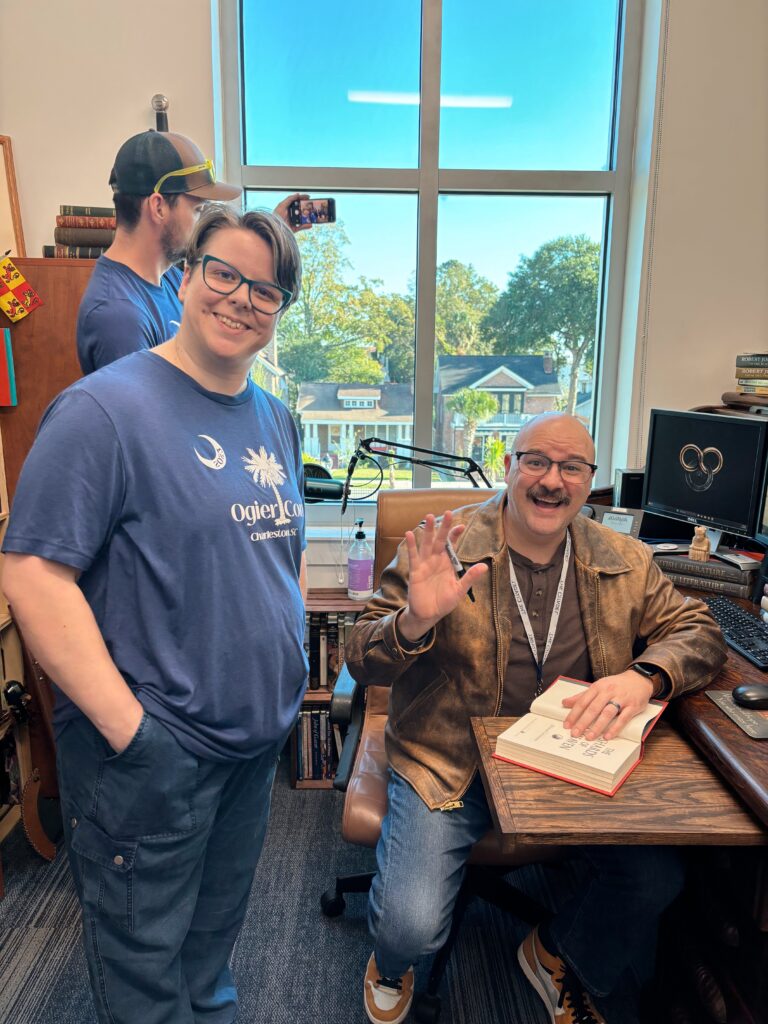

Next, we met with military historian and author of Origins of the Wheel of Time Michael Livingston.

He talked about his own creative process and showed us around The Citadel – the military college where RJ drew inspiration for The White Tower. There was also an impromptu book signing at Robert Jordan’s desk, which is now his. Michael signed a copy of his fiction book Shards of Heaven for me, which I look forward to reading. It is a historical fantasy novel set in Ancient Rome.

I’m still processing everything I was able to see.

Most of it didn’t seem real. Kind of like seeing Big Ben for the first time.

And between every surreal moment was soul to soul connection.

The intimate size and setting of the gathering made space for expansive and meaningful conversation.

It was like a bubble of peace that existed outside of time and space.

A Dreamshard, if you will.

I went looking for Robert Jordan and I found his spirit alive in these people.

If that’s not metaphysics at work I don’t know what is.

Many thanks to everyone who worked hard to make this weekend come to be, and also to every single sweet spirit who was there.

You are all doing The Light’s Work in your own way.

Your names sing in my ears.

I’m in proper long winded Ogier mode today, but I’ll try to wrap things up.

Circling back to my creative process:

I’ll never be Robert Jordan.

No one will.

But I can be Sarah Shotts.

I can tell the stories that are important to me in the ways and timelines that are right for me. My goal isn’t capitalistic success, but creative expression. To make something that’s true to me and share it with others who may find bits of themselves in it.

I’ll always have multiple projects. But I’m learning how to them weave them together. One project bubbling away in the slow cooker. One on the stovetop. And another fermenting in a dark cupboard.11

That cupboard is where my fiction writing has been. It’s time to wake up that sourdough starter and start proving some bread.

Kindle Curiosity is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Let’s discuss.

Do you have any projects in the fermentation cupboard you’re ready to pull out?

Have you ever had a creative pilgrimage? Where did you go and what did you learn?

Cheers,

P.S. Did you miss my first post about rediscovering Wheel of Time? Catch it here.

P.P.S. Want to know more about The Wheel of Time? I wrote this for you.

Footnotes

We realized over the weekend that the easiest way to explain why 12 strangers were flying across the country to visit a library and an old tree was simply to call ourselves a book club. It worked on my chiropractor.

Metaphysics definition via Oxford Languages

Also true, and something I love about this fandom is that we each bring our own criticisms to these books we love. I don’t love these books in a way that is infallible. I know they are flawed. Everything human is. And I love them anyway.

Perhaps I should reread John O’Donohue’s Anam Cara with this in mind. Maybe there are answers there. (Anam Cara means “soul friend” in Gaelic.)

For the curious that’s 88 NaNoWriMo novels. The reason I went for words instead of pages.

Siuan Sanche, The Great Hunt by: Robert Jordan

Box 20, EOTW Revision #1, Filename: Ramblings, pg. 10 (James Oliver Rigney, Jr., papers, College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.)

Box 24, Folder 1, TGH, “Misc Random thoughts” (James Oliver Rigney, Jr., papers, College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.)

Box 24, Folder 1 “Notes on course of books” (James Oliver Rigney, Jr., papers, College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.)

Box 75, Folder 2, “Additional White Goddess Notes” (James Oliver Rigney, Jr., papers, College of Charleston Libraries, Charleston, SC, USA.)

It turns out fermentation is actually a key part of my creative process, and not one I’m going to feel guilty about any more. Maybe I’ll write more about this another day.